COVID-19: Therapeutics and Vaccines (23 March 2020)

Endeavoring to provide a Coronavirus Disease-2019 (COVID-19) update roughly biweekly, I thought I would focus this post on current efforts to both identify therapeutics for SARS-CoV-2 (the virus that causes COVID-19) infection and to produce a COVID-19 vaccine.

Regarding therapeutics, there is presently no FDA-approved medication with a study-proven indication for the treatment of patients with COVID-19. However, as of the date of this post, there are 81 clinical trials in various stages (i.e. pre-recruiting, recruiting, enrolling, underway, and completed) registered with the National Institutes for Health (NIH). Of these, about 54 are interventional studies looking at various therapeutics — including investigational medicines (some of which are traditional Chinese medicines), off-label efficacy of existing medications used to treat other conditions, monoclonal antibodies and other biologicals, inhaled nitrous oxide, and various antiviral medications. Most of these studies are very preliminary and have not yet produced actionable data. (For a list of these trials and to read about them, see: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results…) Nonetheless, there are several medications that have anecdotal support for the treatment of patients with COVID-19. Among these are remdesivir and chloroquine/hydroxychloroquine. Remdesivir belongs to a class of antiviral medications called nucleotide analogues which work by inhibiting viral replication within infected cells. Remdesivir, which has shown in vitro activity against two other coronaviruses: Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus-1 (SARS-CoV-1) and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV), also appears to have in vitro activity against SARS-CoV-2. Presently, remdesivir is only available for the treatment of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 through either clinical trials or compassionate use.

Both chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine have also been reported to inhibit SARS-CoV-2 in vitro. These medications are used to treat patients with malaria as well as various autoimmune disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus, and clinical data supporting their use for patients with COVID-19 is limited. However, in one open-label study of 36 patients with COVID-19, use of hydroxychloroquine (200 mg three times per day for 10 days) was associated with a higher rate of undetectable SARS-CoV-2 RNA in nasopharyngeal specimens at day 6 compared with no specific treatment (70 versus 12.5 percent). Moreover, there appeared to be additional benefit when hydroxychloroquine was combined with the macrolide antibiotic azithromycin. [Gautret et al. (2020) Hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin as a treatment of COVID‐19: results of an open‐label non‐randomized clinical trial. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents–In Press 17 March 2020] One would not expect azithromycin to have antiviral activity, but this antibiotic is known to have anti-inflammatory properties as well.

Among the antivirals being studied for the treatment of patients with COVID-19 are those belonging to a class known as protease inhibitors, which are used primarily for HIV and hepatitis C infections. Despite anecdotal benefit, one such medicine, lopinavir-ritonavir (Kaletra®), failed to show benefit versus standard of care alone with respect to time to clinical improvement or mortality in a randomized trial of 199 patients. (N Engl J Med. 2020)

Another therapeutic garnering attention for the treatment of patients with COVID-19 is the biologic tocilizumab (Actemra/RoActemra®). Tocilizumab is an anti-interleukin-6 receptor approved for the treatment of patients with rheumatoid arthritis, giant cell arteritis, polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis, and systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Interest in this biologic was generated by anecdotal reports of its benefit by physicians in China and buoyed by the China National Health Commission’s decision in early March to add tocilizumab to its updated COVID-19 treatment guidelines. The biopharmaceutical company Roche, along with the US Health and Human Services’ Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) and in collaboration with the Food and Drug Administration, is poised to conduct a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled Phase III clinical trial to assess the safety and efficacy of tocilizumab in patients with severe COVID-19.

Before leaving the topic of therapeutics, it is worth noting that there are conflicting data about the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDS; e.g. ibuprofen) and glucocorticoids in patients with COVID-19. These derive from theoretical concerns about the immune dampening properties of these agents, along with anecdotal reports of some individuals who were taking these medications having more severe disease. However, the data are insufficient to support these observations and the World Health Organization does not currently recommend withholding NSAIDS or glucocorticoids if they are clinically indicated for other medical conditions.

Switching our discussion to vaccines — As I’ve mentioned previously, there has not been much interest historically in producing coronavirus vaccines. This derives from the fact that most coronaviruses: 1) cause mild, self-limiting illness (e.g. the common cold); 2) are difficult to replicate in tissue culture; 3) display antigenic variation (That is to say that the surface proteins against which a potential vaccine might be targeted change); and 4) Vaccine trials with at least one animal coronavirus demonstrated a worse outcome upon challenge with the virus (a problem similarly posed by both respiratory syncytial virus and dengue virus). Nonetheless, there are ongoing efforts to produce vaccines against two coronaviruses that are associated with more severe disease (i.e. SARS-CoV-1 and MERS-CoV).

Recognizing that most people do not have a background in vaccinology, I thought it might be helpful to make a few general comments about vaccine development before speaking specifically about COVID-19 vaccine research. The basic principle of any vaccine is to present some pathogen or part of a pathogen to the immune system so that should the immune system encounter it again (i.e. by infection), it “remembers” (anthropomorphically speaking) the pathogen and quickly responds (This is referred to as an “anamnestic” response). The challenge is to produce a vaccine that is immunogenic (i.e. immune stimulating) enough to trigger a robust protective response without being so reactogenic that the vaccine makes the vaccinated individual as sick as does infection with the “wild-type” (i.e. naturally occurring) pathogen. The approach to making vaccines varies, but basic methods include the use of: 1) live, attenuated (i.e. weakened) organisms; some examples include varicella (chickenpox, measles/mumps/rubella, influenza, rotavirus, oral polio, and zoster (shingles); 2) inactivated (i.e. killed) organisms, such as the intramuscular polio vaccine, hepatitis A, and rabies; 3) toxoid (i.e. inactivated toxin), including diphtheria and tetanus; and 4) subunit/conjugate (i.e. recombinant) constructs, such as hepatitis B, intramuscular influenza, Haemophilus influenza type b, Pertussis, pneumococcus, meningococcus, and Human papillomavirus. In the 1990s, a new approach emerged utilizing the nucleic acid (i.e. DNA or RNA) of a pathogen as a vaccine. The principle here is that once the nucleic acid is injected into a person, its genes will be expressed to make protein that will trigger an immune response. This was the approach used to produce the only coronavirus-19 vaccine currently in clinical trials, so now let’s turn our attention back to COVID-19.

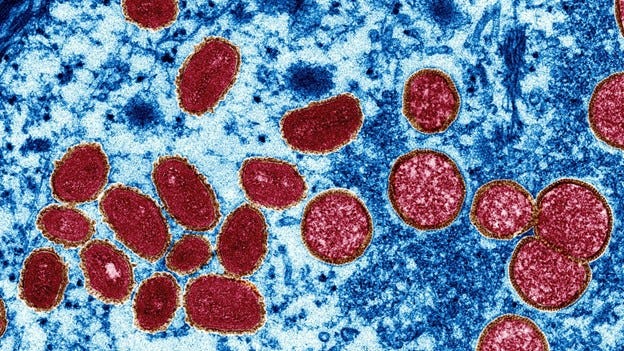

The current COVID-19 pandemic has generated considerable interest in developing a vaccine against the responsible virus — SARS-CoV-2 (so named because of sequence homology and clinical similarity between SARSC-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV-1). There are about 35 biotechnology companies and academic institutions currently researching SARS-CoV-2 vaccines, with more than a dozen in preclinical (i.e. not yet in human) trials globally. Additionally, there is one clinical trial already in progress — a collaborative Phase 1 study between the Vaccine Research Center (VRC) of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (NIAID) and Moderna (a Cambridge, Massachusetts-based biotechnology company that is focused on drug discovery and development). For those unfamiliar with the parlance, a Phase 1 trial (formerly referred to as a “first-in-human” study) involves testing the vaccine in a small number of volunteers to assess safety, side effects, optimal dosing and formulation. Efficacy is not assessed at this time but instead, in subsequent phases of the clinical trial. The NIAID-Moderna candidate vaccine began on 16 March at Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute (KPWHRI) in Seattle. It enrolled 45 volunteers and is expected to last for about six weeks. The vaccine, called “mRNA-1273”, expresses a spike protein found on the surface of SARS-CoV-2 (Recall that in a prior post I mentioned how corona viruses are studded with such proteins, invoking the image of a crown when observed by electron microscopy — Hence the word “corona”, Latin for “wreath” or “crown”). Because VRC and Moderna were already researching a MERS-CoV vaccine, they had a head start and could leverage their experience in the pursuit of a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. For more information about the mRNA-1273 vaccine study, visit ClinicalTrials.gov and search identifier NCT04283461.

One day after the first SARS-CoV-2 clinical trial was launched in the U.S., China’s National Medical Products Administration announced that it also had five candidate vaccines poised to start testing in humans. Each of these is a different construct: an inactivated (i.e. killed) vaccine, a genetically engineered subunit vaccine, an adenovirus vector vaccine, a nucleic acid vaccine (presumably akin to the NIAID-Moderna vaccine), and an attenuated (i.e. weakened) influenza vector vaccine. It isn’t clear to me whether all, some, or only one of these vaccine candidates will enter phase 1 testing.

In closing, it is worth reminding ourselves that despite the collective sense of urgency surrounding COVID-19, any potential medicine or vaccine must be thoroughly and rigorously tested to ensure that it is both safe and effective. (Primum non nocere.)

Until my next update, regards.

Michael Zapor, MD, PhD, CTropMed, FACP, FIDSA (23 March 2020)